Notes: On “Left-Wing and Anarchist Terrorism,” from The European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (2021)

(MLKP militants in Istanbul, Turkey)

Overview and Analysis

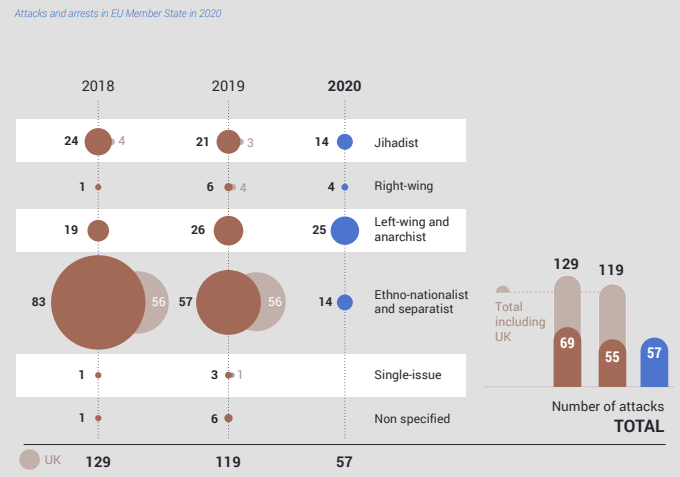

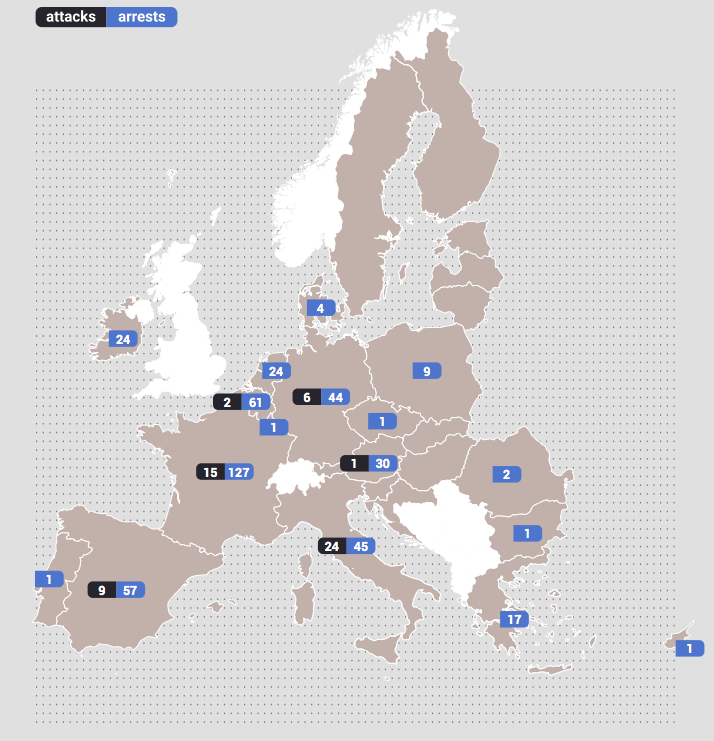

The European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2021 (TE-SAT) was published by Europol on June 22nd. The current threat profile based upon Europol’s assessment of terrorist activity in Europe throughout 2020 looks much as it did in the previous two years’ TE-SAT reports, with an increased emphasis on right-wing extremism. As with prior TE-SATs, this year’s provides an annual overview of terrorist trends in Europe, then divides the current threat landscape into three categories for analysis: “Jihadist Terrorism,” “Right-Wing Terrorism,” and “Left-Wing and Anarchist Terrorism.” This article’s primary concern is the latter of these three categories. Briefings of four specific left-wing/anarchist (LW/A) terrorist events covered in the TE-SAT’s assessment will be provided, followed by some concluding remarks.

The TE-SAT2021 defines “left-wing and anarchist” terrorism separately:

Left-wing terrorist groups seek to trigger violent revolution against the political, social and economic system of a state, in order to introduce socialism and eventually establish a communist and a classless society. Their ideology is often Marxist-Leninist […]

Anarchist terrorism, as an umbrella term, is used to describe violent acts committed by groups (or to a lesser extent individuals) promoting the absence of authority as a societal model. They pursue a revolutionary, anti-capitalist and anti-authoritarian agenda.

Motivating factors of left-wing terrorism mentioned in the TE-SAT include “anti-fascism, anti-racism, and perceived state repression.” The TE-SAT 2021 also locates anti-5G infrastructure attacks within the “radical left-wing” dataset of 2020 attacks—acknowledging the fact that anti-5G sentiments gained traction with a variety of groups across the political spectrum, especially in the summer of 2020 as concerns about 5G infrastructure owned by Chinese telecommunications company Huawei merged with fears about the spread of COVID-19 and myriad other conspiracy theories. In the right-wing terrorism section of the TE-SAT, it is similarly noted that attacks on infrastructure have been fueled by a narrative that “ties in with anti-system and technophobic sentiments, e.g. opposition to 5G technology.”

Regarding the specific impact of COVID-19 on LW/A terrorism/terrorists in Europe last year, the report says:

The pandemic had an effect on all forms of left-wing and anarchist extremist activities. The groups, however, adjusted to the new reality and concentrated their efforts on taking advantage of opportunities to achieve various aims: to demonstrate their opposition to government decisions; to highlight the perceived repressive nature of the state; to destroy symbols of capitalism; to oppose the deployment of the 5G telecommunication network; to spread fake news and conspiracy theories; and to support the fight for an independent Kurdish state.

Aside from the additional target of 5G infrastructure, 2020 was business as usual for anarchists in Europe according to the TE-SAT, as all of these were causes to which they were committed and actions which they were taking prior to the pandemic (not so much the “spread fake news and conspiracy theories” component). In reality, far-left and anarchist organizations throughout the world took the pandemic as an opportunity to mobilize resources, accrue solidarity capital with geographically far-flung politically aligned movements, leverage perceived suppressive state policies in response to the pandemic to advance their various causes, and incorporate public health measures adopted for infection control into their actions. In the United States, for example, the New York City wing of the Revolutionary Abolitionist Movement (an anarchist organization with no affiliation to terrorist organizations or association to acts of terrorism) fabricated and shipped masks over 2,300 miles away to indigenous anarchists of the Navajo Nation in Arizona, at the latter’s request for personal protective equipment on social media. Between the militant far-left and anarchist underground, COVID-19 likely had an operational impact on clandestine actions as measures such as lockdowns and (especially) curfews were imposed. Most notably, COVID-19 was used as a pretext by various European governments in an attempt to deny the freedom of assembly and protest, which in addition to itself being a provocation, created a more restrictive environment for activism and direct action, all of which came with higher risks of arrest.

(Source: TE-SAT2021)

Though not included in its dataset of LW/A terrorist events, the TE-SAT does make passing mention of low-intensity campaigns of clandestine violence carried out by underground groups across Europe versus the state and private entities:

Anarchist extremists continued to form unstructured non-hierarchical groups that operated mainly in and around specific urban areas. In a number of EU Member States, anarchist extremist groups or individuals resorted to small-scale attacks against public and private property, including telecommunications infrastructure (such as 5G antennas), office buildings, real estate agencies, ATMs, vehicles, and COVID-related technological developments.

However, the report does not provide details of LW/A attacks against “COVID-related technologies”.

Likewise, there also is no mention of policy decisions made by various EU governments during 2020, which factored into pre-existing conflict between the state and extra-parliamentary movements on the left and post-left, most notably conflicts over particular spaces, such as efforts in Greece and Germany to evict properties that had been squatted for over a decade and hold immense accrued value among these movements internationally. The efforts to evict anarchist squats is still underway in both countries, and has been met with serious resistance in the streets, as aligned and adjacent movements abroad demonstrate and carry out actions in solidarity with the evicted properties. The squat evictions have also been a prominent source of escalating clandestine violence in EU countries like Greece and Germany. Illustrative of this relationship between squat evictions and clandestine action, as well as of the relationship between anarchist groups internationally, is the October 2020 firebombing of two Amazon company vans outside of Berlin in solidarity with recently evicted Greek squat, Terra Incognita, followed by the firebombing of a Würth Group vehicle in Athens by Greek anarchists, in solidarity with the Rigaer 94 squat facing imminent eviction in Berlin.

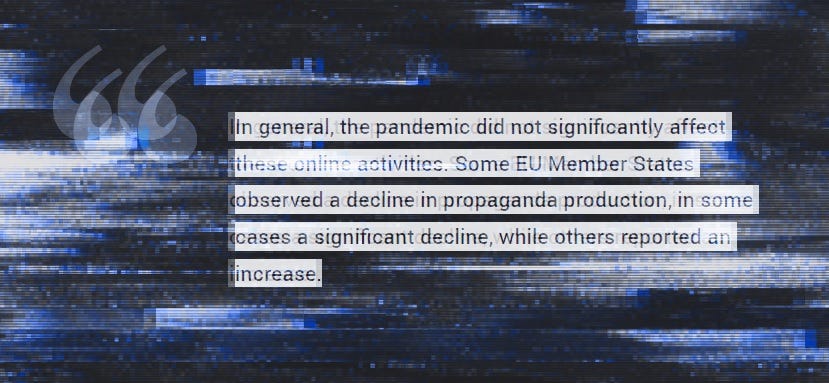

The TE-SAT 2021 concludes this section of the report with a briefing of the online activities of LW/A elements in Europe:

In 2020, left-wing and anarchist terrorist and violent extremist groups continued to use the Internet as the main means to claim responsibility for the attacks they perpetrated. They also disseminated propaganda and carried out awareness-raising and recruitment activities online. In general, the pandemic did not significantly affect these online activities. Some EU Member States observed a decline in propaganda production, in some cases a significant decline, while others reported an increase.

Left-wing and anarchist extremists have a high level of security awareness, and the technical developments of recent years have resulted in an increased capability to communicate anonymously. They were also observed to run their own communication platforms. An example of an anarchist extremist online network is ‘No log’, operated by a Czech anarchist group, which is inspired by similar services such as [redacted] or [redacted]

The report then finishes up with a brief description of an alleged LW/A cyber attack on a Swiss company in 2020 (without specifics), and mentions the online activites of an Iranian national in Greece, which led to his arrest and is covered in slightly greater detail in the following section.

(TE-SAT 2021, p.97)

The major events that occurred within the LW/A terrorist space in Europe covered by the TE-SAT 2021 range from a parcel bombing attack that was executed by an international anarchist organization with its origins in Italy, the Informal Anarchist Federation (FAI), to a foiled attempt by a group in France to carry out guerrilla warfare, and the high-profile arrest of 26 people in Greece accused of weapons charges and membership within the outlawed Turkish Marxist-Leninist party-cum-guerrilla-organization, the Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C). As with the previous two years’ TE-SATs, the LW/A section of the 2021 report gives special attention to the DHKP/C, though the group has primarily targeted Turkey and the United States. Concurrent reporting on the DHKP/C across annual TE-SATs is likely to do with the organization’s activities within EU countries, where a low saturation of law-enforcement along with a close geographic proximity to Turkey creates a permissible environment for future operations against the Turkish government (i.e., Greece), where there is a large Turkish diaspora, or a combination of these factors exists.

Briefing: DHKP/C, the FAI, the French Plot, and the Iranian “John Brown” in Greece

The Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C)

The TE-SAT 2021 is notably narrow in scope, and dedicates an arguably large amount of space to, for instance, the DHKP/C—given the limited threat that the group has posed to EU countries themselves. To this author’s knowledge, whenever DHKP/C has chosen non-Turkish targets for terrorist attacks, they have always been American/NATO specifically, including their 2013 suicide bombing attack on the US Embassy in Ankara, which killed one Turkish police officer and badly damaged the embassy’s security checkpoint. However, DHKP/C cells do have a serious history of operating in Greece, and are considered a terrorist organization by Turkey, the EU and the United States. In 1998, Germany banned the group, though pro-government media in Turkey claims that as many as 650 active DHKP/C affiliates remain among the Turkish diaspora living in Germany.

(US Embassy, Ankara, 2013)

The Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front, or DHKP/C, adopted its current name and form in 1994, but actually has its origins in a 1965 revolutionary youth movement, Devrimci Gençlik, which itself split into several different parties and armed factions as Turkey spiraled out of control and into a low-intensity civil war of the country’s far-left versus its far-right, which began in earnest in 1976 and only ceased after a brutal military coup d’état in 1980. (Similar periods of left-versus-right violence across European countries in the 1960s through the 1980s are often referred to as “Years of Lead” after Italy’s decades of political violence in the mid-twentieth century, known as the Anni di piombo. Turkey’s short and bloody four years of lead claimed some 4,500 lives, by RAND’s estimate—though others put the number killed at over 5,000.)

Outside of Turkey, the DHKP/C’s most serious activities have taken place in Greece—without accounting for fundraising and other material/immaterial support they gather elsewhere—and most notably, in 2017 nine alleged members of the organization were arrested following a raid in Greece, and accused of plotting to ambush the motorcade of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan with rockets, while on his historic visit to Athens. In March of 2020, Greek counter-terrorism forces raided two homes in Athens and detained 26 people, resulting in the discovery of an RPG-7 launcher, a Yugoslav M80 Zolja portable anti-tank rocket, a Kalashnikov-pattern rifle, several handguns, assorted ammunition, and other military equipment in a house in the Sepolia neighborhood of Athens. Subsequent raids followed in Turkey in the fall of 2020, and according to pro-government sources, netted over 90 members of the group, including senior leadership. Eleven Turkish nationals are still waiting to stand trial in Greece, following the 2020 raids in Athens.

(Hellenic Police escorting an alleged member of DHKP/C, March, 2020)

The Mikhail Zhlobitsky Cell of the Informal Anarchist Federation (FAI)

The TE-SAT2021 also highlights a failed parcel-bombing attack carried out by the Italian-based international anarchist network, the Federazione Anarchica Informale, or Informal Anarchist Federation (FAI). In September 2020, the president of the employers’ union (Confindustria) in Brescia, received a victim-operated IED (VOIED) by mail in a package, which did not explode. A claim was released a few days later, which claimed another parcel bomb that was sent to the penitentiary police union offices, SAPPE, in Modena. The “Mikhail Zhlobitsky Cell” of the FAI claimed both bombs.

In 2018, 17-year-old Russian Mikhail Zhlobitsky walked into the Federal Security Service (FSB) station in Arkhangelsk and detonated an explosive device, killing himself in a deliberate suicide bombing, and wounding three FSB officers. According to a post he made on Telegram prior to the attack, Zhlobitsky’s immediate motivation for the bombing was the Russian government’s crackdown on far-left activists in the country, which apparently included fabricating criminal cases.

(Mikhail Zhlobitsky reaching into his pack to detonate an explosive device, 2018)

The FAI praised Zhlobitsky’s attack in their 2020 claim of the two unexploded parcel bombs in Brescia and Modena, Italy:

No judgment can stop the Informal Anarchist Federation. We have not forgotten the action of our brother Mikhail Zhlobitsky. Beyond the generations of virtual alienation, Mikhail is the youth of the world. This action is dedicated to him.

The 2020 parcel bomb claim is not the first in which FAI has used a tributary operational cell name. For instance, the 2012 Adinolfi shooting, in which the CEO of Ansalde Nucleare had been “kneecapped,” was claimed by the “Olga Ikonomidou Cell”—an homage by Italian FAI militants to an imprisoned member of the Greek anarcho-nihilist urban guerrilla outfit, the Conspiracy Cells of Fire (CCF).[1] (Both FAI and CCF have subsequently demonstrated a strong affinity for and solidarity with one another.)

FAI in their present form as a loose network of cells and individuals bound by ideology and doctrine, as well as a commitment to revolutionary violence, have been operational since 2003. In his 2014 profile on FAI, Dr. Francesco Marone notes of their activities up to that point:

In the last decade, the FAI has been able to sustain an intense campaign of violence. In particular, a series of bombs and letter bombs, often directed against high-profile targets, have caused concern and alarm. The network has yet to cause any deaths, but some of their attacks were potentially lethal. Furthermore, the FAI has established ties with foreign groups, especially in Greece, and has become a model of inspiration for extremist groups and individuals around the world.

In June 2020, the Italian Carabinieri conducted an operation that netted seven people on terrorism charges with alleged links to militants in France, Spain, and Greece—including the Conspiracy Cells of Fire.

According to the Carabinieri, the seven also had ties to the 2017 detonation of an IED outside of one of their stations in Rome.

The French Plot

The TE-SAT 2021 briefly mentions the French police arrest of seven people in December 2020, five of whom were charged with weapons and terrorism offences, and were alleged to have links to militants abroad. “Weapons and material which could be used to produce explosives were discovered at the time of the arrests, according to the Internal Security branch (DGSI) of the French national police.” French media said the “cell” was led by a 36-year-old French national with combat experience fighting alongside Kurdish militias against the Islamic State in northern Syria. Le Parisien reports that the group intended to carry out guerrilla activities in France, including the targeting of French law enforcement and military personnel.

Abtin Parsa—the Iranian Anarchist in Greece

In its coverage of the online activities of LW/A terrorists in Europe, the TE-SAT 2021 mentions an Iranian refugee and self-proclaimed anarchist, Abtin Parsa, who was arrested by Greek police following a post on an anarchist website that called for the arming of refugees at the Greek land border with Turkey, near Evros:

In my opinion, at the moment, solidarity means attack and we need a movement of solidarities that have anti-capitalism and anti-state characteristics in Greece. We must attack the interests of state and capitalism in solidarity with immigrants.

Since a few days ago, thousands of immigrants are in the border of Greece/Turkey and try to get inside EU, but the cops and soldiers used war bullets and tear gas against immigrants. While I believe we should not get inside the political game of the states, right now, the most useful solidarity to the immigrants who are at the border is to arm them because the answer to bullets should be bullets back and this is the only way to open the border for all the immigrants. We as immigrants should fight for what we need and at the moment, our first need is survival, so we must destroy those who are killing us; we have nothing to lose but our fear.

Parsa was apprehended in the downtown Athens area of Victoria Square—a neighborhood with a long history of welcoming refugees and immigrants, which predates the ongoing “immigration crisis”. He was also known to have moved between the Exarcheia and Kypseli neighborhoods of downtown Athens, and reported to have contacts with members of the anarchist urban guerrilla group, Revolutionary Struggle—famously known to have fired a rocket-propelled grenade into the US Embassy in Athens.

Conclusion

In its key findings on LW/A terrorism in Europe throughout 2020, the TE-SAT 2021 states: “In 2020, all 24 completed left-wing and anarchist terrorist attacks occurred in Italy. One plot was thwarted in France.” EU Directive 2017/541 defines terrorist offences as:

intentional acts which, given their nature or context, “may seriously damage a country or international organization when committed with the aim of: seriously intimidating a population; unduly compelling a government or international organization to perform or abstain from performing any act; seriously destabilizing or destroying the fundamental political, constitutional, economic or social structure of a country or an international organization.”

The report acknowledges the fact that, despite the shared framework within EU countries of Directive 2017/541, individual countries nonetheless have their own definitions, and acts which one country might consider terrorism “might not have crossed a line in another.” Thus, the fact that the TE-SAT’s figures on the number of terrorist events that occurred in 2020 may not agree with other datasets is not so much an unintentional oversight as it is a compromise. Activities of urban guerrilla groups, for instance, which do not fit the definition of terrorism in a country like Greece are briefly mentioned. By the TE-SAT 2021’s measure, arrests related to LW/A terrorism in 2020 (52) were down by more than half, when compared to arrests in 2019, “largely due to a drop in arrests in Italy (24 in 2020, compared to 98 in 2019).”

Looking ahead to next year’s TE-SAT, 2021 has been a busy year for LW/A militants, though it remains to be seen whether their current actions will meet the EU Directive 2017/351’s definition of “acts of terrorism,” or whether the acts of militant groups themselves will escalate to those we have seen for decades now from the FAI, such as parcel bombings and shootings. In Greece, cells affiliated with an emergent anarchist urban guerrilla network, the Direct Action Cells (DAC), took responsibility for 20 attacks across mainland Greece this year in a single batch claim, announcing their formation and urging likeminded cells and individual to take similar actions under the DAC banner. DAC has since claimed half-a-dozen more attacks, most of which (along with the initial 20) targeted various entities and individuals ranging from the German cultural Goethe Institute to the home of a retired Lieutenant Police General (highest attainable rank in the Hellenic Police), all of which employed either Molotov cocktails or, more often, improvised incendiary devices (IID) fashioned from propane gas canisters. Where the latter devices cross over into being IEDs is not certain to this author.

2021 has also seen plenty of high-mobilization events across Europe and the world in general, in which LW/A movements have accrued solidarity capital and other various resources. There has been significant attention paid in LW/A spaces to the ongoing multifaceted conflict between the people of Myanmar and the government, following a coup d’état by the military earlier this year, for example. Similarly, LW/A movements across the world are paying close attention to the ongoing political violence in Colombia, and the actions taken by aligned movements in that country. Unrest in the United States remains of intense interest to LW/A movements in Europe, and vice versa (though not as equally bidirectional, with Europeans paying greater attention to developments in the US than the other way around, at least for now). The 62-day hunger strike of convicted Greek terrorist and operational head of the Marxist-Leninist guerrilla outfit Revolutionary Organization—17 November, Dimitris Koufodinas, prompted actions in solidarity across Europe. German anarchists briefly managed to storm the Greek consulate in Berlin and drape a banner from the 4th floor in solidarity with Koufodinas. Perhaps as many as 100 direct actions took place in solidarity with Koufodinas across the continent. Similarly, and as previously mentioned, ongoing battles over spaces are leading to serious clandestine guerrilla action, a fight that is presently centered internationally upon the imminent eviction of the Rigaer 94 squat in Berlin, Germany.

Multiple high-profile LW/A court cases have been on the 2021 dockets across EU countries, most notably those of 11 Turkish nationals in Greece and members of CCF and Revolutionary Struggle in the same country. These cases will continue to inspire both symbolic and direct actions from aligned groups in solidarity with the accused. Economic, social and public health issues caused by the ongoing pandemic will continue to affect LW/A militant movements as they have others, and government policies will be met with strategic and doctrinal shifts among groups under these banners. A new policing bill regarding the freedom of assembly and protest in the UK has drawn significant attention from international LW/A movements, and could be a legislative harbinger of similar policies in other countries, as the West in general faces mass mobilization and discontent, due to a variety of both exogenous and endogenous shocks to societies and systems of governance. The TE-SAT 2022’s section on LW/A activities, if covered properly, should provide another full read.

[1] It is important to note that, while most common anarchist guerrilla operations tend to be non-lethal and often select symbolic targets of the state or private industry, certain attacks have lethal potential, especially direct actions carried out against specific individuals. In 2013, two Greek anarchists approached the offices of neo-Nazi political party, Golden Dawn, in a borough of Athens and opened fire on three party members, killing two and wounding the third. The attack was in retaliation for the murder of anti-fascist rapper, Pavlos Fyssas, at the hands of a Golden Dawn member.